Gryla is a very bad and grim ogre, and she eats badly behaved children, she comes to pick them up, puts them in her sack and then cooks them in her cauldron. Gryla and leppaludi were cannibals like other trolls and mostly prayed on children, but didn't mind eating fully-grown men as well.

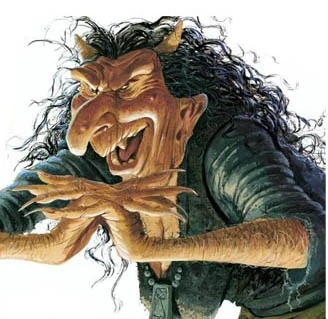

Another account claims that she has bad nails on each finger, eyes in the back of her head and horns like a goat, the ears dangle down to her shoulders and are fastened to her nose. Her chin is bearded and her teeth are like charcoal!

“Mummy,”

I heard the voice whisper to me from underneath the thick blanket.

The wind was howling outside,

causing branches to scratch against the window

like little wooden claws trying to get in.

“It is almost Christmastime!

Do you think Santa will bring me presents?”

I smiled at the girl as I walked over to her bed.

I reached down and stroked her hair,

the only part of her head not covered by the heavy wool.

Her head looked so small next to my hand.

Again the wind shrieked.

It almost sounded like it carried the sound of an angry cat with it.

“Well that depends,”

I answered. “Have you been good this year?”

“I think so,” the little voice replied.

“I mean, I did play a few pranks on my teacher.

And daddy did yell at me a few times,

but he does that a lot.”

I smiled,

a crescent of razors.

My hand, much larger than the girl’s head,

grabbed it like the child would a toy ball.

I easily lifted her up in front of my massive frame.

Her scream sounded sweet.

One of the most terrifying Holiday Horrors I have come across is the story of Gryla, a giant from the hills of Iceland. Descriptions of Gryla vary. Some of them claim that she has horns and fangs, thirteen tails trailing behind her, and a wart-covered nose.

Others claim that she is just a hideous, large woman, more an ogress than a giantess. No matter the description of her appearance, however, her motives and actions are always the same. Gryla is hungry, and her favourite treats are children.

The giant has the innate ability to sense whether or not children have been naughty throughout the year.

Before the 17th century, Gryla would be indiscriminate in when she strolled into towns and feasted. However,

as the strength of Christianity spread, and Christmas lore developed,

Gryla started only coming down during the holiday season.

She does not only eat children,

though they are her favourite.

Her hunger is so great, starved throughout the year,

that she has even been known to eat her own husbands!

Though I do not know why anyone would choose to marry her,

she is currently on her third mate.

Interestingly enough, Gryla does have thirteen children known as the Yule Lads.

The Dimmuborgir lava fields of northeastern Iceland is said to be the home of the ogre/troll Gryla, her lazy third husband Leppaludi (she murdered her first two husbands), and at least 13 of her troll children. The number 13 is the recently agreed upon number because, as with any folk tale, the exact names & numbers have changed over time. At one point Gryla was said to have as many as 82 possible children depending on the version of the story. Her appearance also changes with the telling of the story – she sometimes has horns, cloven feet, 40 tails or maybe 15 tails, 3 faces or just 1 face, etc.

Gryla hears about bad Icelandic children all year long and, in the dark cold of winter, she wanders the land tracking them down. She kidnaps misbehaved children, sticking them in a sack over her shoulder (or in a sack being held by one of her tails), and takes them back to her cave where she cooks them into a stew for herself and Leppaludi. Around the same time her sons set out to perform mischief.

Gryla is accompanied by two other evil creatures. The lesser known is her husband, the troll Leppaludi. Gryla is a domineering woman, she is often shown beating and berating her husband. According to the legend leppaludi is the third of Gryla’s husbands. She killed and ate her first husband Gustur. Her second husband Boli, whom she also murdered, after the two had a large number of troll children.

According to the oldest poems, Gryla originally lived in a small cottage. She was a persistent and troublesome beggar who walked around, asking parents to give her their disobedient children. Her plans were most certainly thwarted by giving her food or chasing her away.

In any case, one day, Gryla was forced to move out of town with her family.

Gryla likes to eat human flesh, especially that of naughty children, for which she has a voracious appetite.

Her favorite food is a stew of disobedient kids, which she cooks in her large cauldron to provide food for herself and her family.

Legend has it that there is never a shortage of food for Gryla, who can quickly and easily locate children who misbehave badly year-round.

Gryla - accompanied by her pet, the 'man-eating' Christmas Cat (jólakötturinn) remains a prominent figure in the Icelandic Christmas tradition.

Of all the people living in the North, it is among the Icelanders that ancient beliefs are most popular.

The Giantess and Her Monstrous Kin

Associated with the winter holiday in Iceland is a lesser known and deeply unsettling giantess named Gryla. Her origins are within Norse mythology and the first written account of her was in the transcription of the previously oral traditions of Scandinavia, the Prose Edda. While she was mentioned in that work during the 13th century as ugly and evil like most other giants in Norse mythology, she wasn’t associated with the winter holidays until the 1800s. The first mention of this association is found in the poem called Poem of Gryla, which describes her 13 horrible children, known as the Yule Lads.

The Yule Lads are the children of Gryla and her third husband Leppaludi. These malicious children play pranks and harass people during the final 13 days leading up to Yule. Children leave their shoes in windowsills and the Yule Lads will leave gifts for them within these shoes. If they have been poorly behaved however, they will find a potato in their shoe instead of a gift. The number of Yule Lads and their mannerisms tend to vary within early depictions based on region and time. Some have described them as mere nuisances, but others have claimed that they are vicious and will kill or devour disobedient children. Like many other figures associated with the winter holidays, they have served as an excuse to frighten children into good behavior. Today, they are depicted as pleasant and jolly men, but earlier tales describe them as monsters. Much like their terrifying mother, they found joy in the suffering of children and hungered for their flesh.

Tale and Motif

Earlier descriptions of Gryla paint her as an ugly, wretched giantess who would beg, trick, or try to trade parents for their children so that she could feed upon them. The more ill-tempered and disobedient the children were, the more she enjoyed their taste. She could be satiated with gifts of other food or would have to be chased away. According to the stories, she lived in a small hut near the edge of town, but when people grew tired of having to chase her away and keep their children safe from her, she was banished to a cave in the mountains or to the Dimmuborgir lava fields in Northern Iceland.

Similar to the tales surrounding St. Nicholas, Krampus, Perchta, and other entities associated with the winter holidays, it is said that she can tell whether or not children have misbehaved throughout the year. Her punishment upon “bad” or “naughty” children is to wander the small villages and cottages around her cave, collect the bad children from their homes by shoving them into her sack, and take them back to her home where she will boil them into a stew in her cauldron. One interesting difference between Gryla and other such bogeymen or judgmental yuletide beings is that she does not punish children or reward them for the sake of keeping them in line; she just wants to eat them — and the bad children taste the best. She is said to snatch up any and all poorly behaved children that she can find and make a stew big enough for her to eat until the next year.

Its dark tones and moody lighting,

giving it an even more sinister feel as Gryla is shown eating a child as the mother looks on from the door.

The facial expression of Gryla,

is almost stoic in her actions,

there is no guilt or joy in the action she is taking,

as she feeds her insatiable hunger for children’s flesh.

The mother’s face is almost masked by the background light,

but she doesn’t appear to be panicked or upset that her child is being devoured,

almost as if it is a fact of life.

Dec 1, 2019 Steve Palace

The Icelandic answer to Santa is sure to put a chill in people’s bones! Gryla, also referred to as “the Christmas Witch”, has a colorful and gory history.

Krampus’s sour seasonal antics may have gotten their own movie but some think Gryla would do equally well as a horror villain. She’s been known about since roughly the 13th century, when tales of her exploits spread via word of mouth. The name Gryla translates as “Growler”, making her even scarier.

Smithsonian quotes a historic passage about the tinsel-hating troll: “Down comes Gryla from the outer fields / With forty tails / A bag on her back, a sword in her hand, / Coming to carve out the stomachs of the children / Who cry for meat during Lent.” Certainly a contrast to “Sleigh bells ring, are you listening?”

Depiction of Gryla the Christmas witch

Actually she didn’t become associated with Christmas till several centuries later, when the idea of a rampaging witch punishing naughty children fused with the yuletide atmosphere. Jól (Yule) is the title often given to an Icelandic Christmas. Smithsonian describes this ancient take on the festival as “a time not only to bring together relatives, living and deceased, but also elves, trolls and other magical and spooky creatures believed to inhabit the landscape.” Gryla definitely fits into that category. She’s called an “ogress” by some, though presumably not to her face. Speaking of her face, what exactly does she look like? Accounts, such as they are, vary. “One rhyme says she has 15 tails, each of which holds 100 bags with 20 children in each bag, doomed to be a feast for the troll’s family”, according to Mental Floss, who highlight the bleak yet mind-boggling folk history.

Poems “describe eyes in the back of her head, ears that hang so long that they hit her in the nose, a matted beard, blackened teeth, and hooves.” Safe to say, should an unlucky reveller run into Gryla, they wouldn’t forget her in a hurry.

Is this seasonal savage really so different to the mortals she preys on? There’s a case that she isn’t, as evidenced by her family. For starters someone agreed to marry this twisted creature! She “comes down from her cave in the mountains to gather up ill-behaved kids for her and her lazy and browbeaten husband leppaludi to make into stew”.

And leppaludi wasn’t the only man to slide a ring onto that wizened finger. “She ate one of her husbands when she got bored with him,” reveals Terry Gunnell of the University of Iceland, talking to Smithsonian.

Then there are the Yule Lads. This bizarre band of brothers existed in their own right to begin with. Gradually however they were incorporated into Gryla’s legend, to form a clan of child catchers and festive buzz killers. Gunnell thinks of them as “looking like aged Hell’s Angels without bikes”. There was a Santa-oriented makeover, but the grittier approach appears to be taking hold again in the Icelandic consciousness.

Those who prefer the darker side of the holiday season have had it pretty good lately, thanks to the fast-growing popularity of Krampus. Once a mythological character on the fringes of Christmas lore, the horned and hoofed Germanic monster has gone mainstream in the U.S. There are Krampus Parades taking over the streets of major cities, an influx of merchandise bearing his long-tongued creepiness, and a horror-comedy film about him starring Adam Scott and Toni Collette.

While Krampus may be king of holiday scares, his fans may be overlooking an equally nasty, much more formidable queen—a Christmas monster who lives further north, in the frigid climes of Iceland who goes by the name Gryla, the Christmas witch. This tough ogress lives in a cave in Iceland’s hinterlands, the matriarch of a family of strange creatures, launching attacks on nearby townships, snatching up misbehaving children, and turning them into delicious stew.

“You don’t mess with Gryla,” says Terry Gunnell, the head of the Folkloristics Department at the University of Iceland. “She rules the roost up in the mountains.”

Tales of the ogress began as oral accounts, with the earliest written references found in the 13th century, in historic sagas and poems throughout the region. One reads, “Here comes Gryla, down in the field, / with fifteen tails on her,” while another describes, “Down comes Gryla from the outer fields / With forty tails / A bag on her back, a sword/knife in her hand, / Coming to carve out the stomachs of the children / Who cry for meat during Lent.”

In Iceland, the midwinter holiday known as jól—a version of the Old English and Old Germanic word Yule, which describes this time of gathering together, feasting and celebrating and which evolved into modern Christmas—is generally darker than in the U.S. (and not just because the sun barely comes out during that time of year). According to Gunnell, the earliest celebrations of the season were viewed as a time not only to bring together relatives, living and deceased, but also elves, trolls and other magical and spooky creatures believed to inhabit the landscape. Sometimes these figures would visit in the flesh, as masked figures going around to farms and houses during the season.

Gryla, whose name translates loosely to “growler,” would be among these, showing up with a horned tail and a bag into which she would toss naughty children.

“She was certainly around in about 1300, not directly associated with Christmas, but associated with a threat that lives in the mountains. You never knew exactly where she was,” says Gunnell. Long poems were written about her and a husband, but he didn’t last long, as Gunnell explains. “She ate one of her husbands when she got bored with him. In some ways, she’s the first feminist in Iceland.”

Other bits of folklore describe a second, troll-like husband and a giant man-eating Yule Cat known to target anybody who doesn’t have on new clothes—making a new pair of socks or long underwear an imperative for any Icelandic holiday shopper. Filling out what Gunnell calls “this highly dysfunctional family” are Gryla’s mob of large, adult sons: the 13 Yule Lads.

Each of these troublemakers visits Icelandic households on specific days throughout December, unleashing their individual types of pestering—Hurðaskellir is partial to slamming doors, Pottaskefill eats any leftovers from pots and pans, and Bjúgnakrækir lives up to his nickname of "sausage swiper."

Gryla did not get connected to Christmas until around the early 19th -century, when poems began to associate her with the holiday. It was also about this time when the Yule Lads and Yule Cat—which had been standalone Christmas characters with no connection to the Christmas witch—then became part of her big creepy family.

Prior to that, she was “really a personification of the winter and the darkness and the snow getting closer and taking over the land again,” according to Gunnell. Not only did she represent the threat of winter, she was seen as actually controlling the landscape. Gunnell explains that the Icelandic people understood themselves to be more like tenants of their harsh environment (where glaciers, volcanoes, and earthquakes dominate), and would view mythical creatures like Gryla as the ones who were really running the show. Krampus only wishes he had such power.

“Gryla is the archetypal villain, and the fact that she’s a matriarch makes her somehow more frightening,” says Brian Pilkington, an illustrator who has drawn some of the definitive depictions of Gryla and the Yule Lads.

In the 20th century, as American Christmas and its depiction of Santa Claus proliferated through Europe and beyond, attempts were made to “Santafy” the Yule Lads. Their bellies widened, their troll-like whiskers grew a bit bushier, and they acquired red-and-white fur costumes. They also, like Santa, began leaving gifts rather than taking sausages, snacks, and so on. (The Dutch tradition of children leaving out their shoes to find chocolates and treats the next morning also influenced this shift.) Some critics tried to snuff out Gryla altogether, attempting to sideline the scary character with more family-friendly fare; one popular Christmas song describes her death.

In more recent years, Iceland as a whole, led by the National Museum of Iceland, have worked to return the Yule Lads to their pre-Santa roots, “trying to get them dressing in 17th- and 18th- century ragged clothes, bringing them back to the browns and the blacks—the local wool colors,” as Gunnell puts it, “looking like aged Hell’s Angels without bikes.” The characters appear in person, with adults dressing up like them to entertain and sing with the children who visit the National Museum.

“It’s a little bit like hanging on to the language and traditions of that kind, to avoid the global Santa image, even if it has the same roots to the past, they’d rather hang on to their Icleandic version,” says Gunnell.

Pilkington, working alongside the National Museum, has worked to do this in his illustrations, including The Yule Lads: A Celebration of Iceland’s Christmas Folklore, a kids’ book about the characters that is ubiquitous around Iceland during the holidays, in both English and Icelandic.

Likewise, Gryla has proven a tough figure to dislodge, with her likeness found throughout the capital city of Reykjavik and beyond, sometimes in the flesh.

“Children are truly terrified of Gryla in Iceland,” says Pilkington. “I’ve visited children's playschools to demonstrate drawing skills and if I draw Gryla then two or three terrified children have to leave the room because it’s too strong for them. This is living folklore.”

Gunnell agrees: “She’s never stopped being embraced here,” he says. “As a living figure, you see her all around Reykjavik. She’s never really gone away.”

Read Jolakotturinn, the Icelandic Yule Cat.

Read The Yule Lads, Iceland.